Ukraine denies the registration of nationality but uses it for ethnic segregation

Received: 26.08.2025

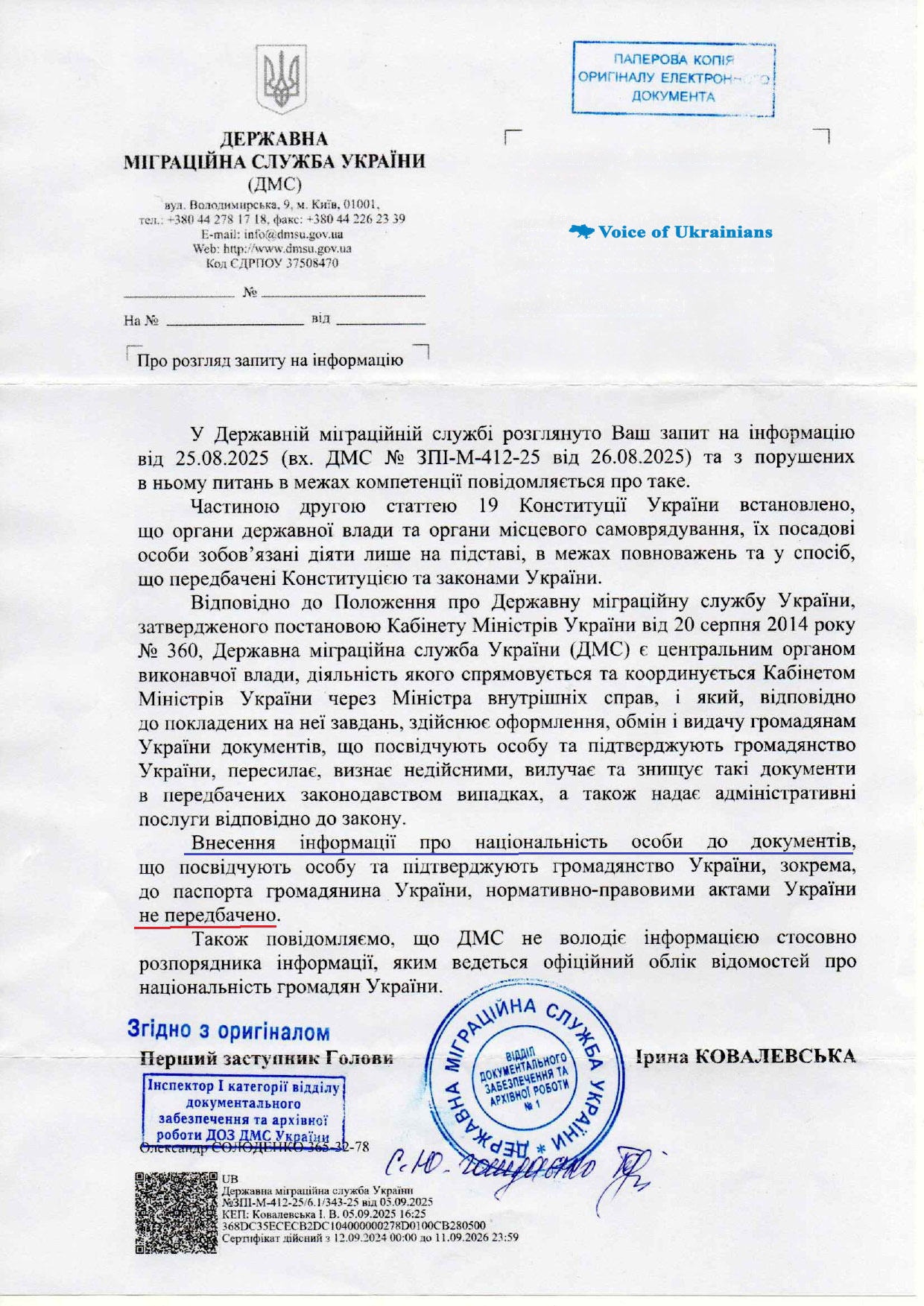

The inquiry raised the issue of whether Ukrainian legislation provides a formalized mechanism for determining and officially confirming a citizen’s national (ethnic) affiliation, as well as whether a state system for recording such information exists.

Particular attention was given to the fact that, in the absence of an official document or a codified procedure, self-identification (e.g., as “Ukrainian,” “Russian,” or “Belarusian”) cannot be considered legally verifiable and, therefore, does not carry legal consequences.

In its official response, the State Migration Service of Ukraine stated that national passports — regardless of their format (paper or ID card) — do not contain a field for “nationality”.

It also confirmed that no centralized system exists at the level of central authorities to record citizens’ national affiliation.

The state does not maintain a registry or any institutional means of certifying ethnocultural identity.

Thus, Ukrainian law does not provide a general mechanism for registering or legally verifying a person’s nationality.

However, this restriction is not universal — it does not apply equally to all categories of citizens.

Explicit exceptions to this rule are contained in two special laws: Law of Ukraine No. 1616-IX “On Indigenous Peoples of Ukraine” and Law No. 2827-IX “On National Minorities (Communities) of Ukraine”.

These laws define the legal status of specific ethnic groups which, by definition, are not ethnic Ukrainians.

These groups are granted formal collective rights to identity, culture, language, education, representation, and access to international protection, as explicitly stipulated in the structure of the respective laws.

Meanwhile, ethnic Ukrainians — the titular majority — fall under neither the category of indigenous peoples nor that of national minorities, and are therefore excluded from the scope of these legislative acts.

This means they lack any legal mechanism for collective representation and protection of their identity, despite the term “nationality” appearing in the Constitution and other legislative acts.

The question of legal recognition of ethnic affiliation thus remains unresolved: if official documents do not include a nationality field, if the state keeps no records, and if there is no defined procedure for verifying ethnic origin, then on what legal basis does the state determine a citizen’s membership in one of the legally protected groups — such as Crimean Tatars, Karaims, or Krymchaks?

This issue becomes particularly significant in light of Article 1 of the Law of Ukraine “On National Minorities,” which explicitly defines a national minority as:

“…a stable group of citizens of Ukraine who are not ethnic Ukrainians, reside within the internationally recognized borders of Ukraine, are united by common ethnic, cultural, historical, linguistic and/or religious characteristics, are aware of their belonging to the group, and express a desire to preserve and develop their linguistic, cultural and religious identity.”

This wording introduces an explicit exclusion of ethnic Ukrainians from the definition of national minorities, while at the same time failing to establish any form of proof or procedure for confirming ethnic identity.

This leads to legal uncertainty and the risk of arbitrary or politically motivated recognition.

The result is a normative asymmetry in which only specific ethnocultural groups possess recognized collective rights, while all other citizens — including the titular majority — are reduced to individual subjects with no access to mechanisms of self-realization, historical continuity, or collective identity.

As a consequence, Ukraine’s legal model incorporates a system of segregation, in which collective rights are reserved exclusively for non-Ukrainian groups.

This is incompatible with the principle of equality enshrined both in the Constitution of Ukraine and in international legal instruments, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

However, when analyzing this legal situation, it is essential to consider the case law of the European Court of Human Rights — in particular, the case of Ciubotaru v. Moldova (application no. 27138/04).

The Court held that Moldova’s refusal to amend the applicant’s recorded ethnicity in official documents, despite his declared self-identification, violated Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which guarantees the right to respect for private life.

The Court emphasized that ethnic identity is an element of personal autonomy and that the state is obliged to provide a procedure enabling individuals to alter ethnic records in accordance with their self-identification.

Thus, ECHR case law confirms that the state cannot disregard a citizen’s declared ethnicity solely based on the absence of archival or official records.

This directly calls into question the legitimacy of Ukraine’s refusal to register nationality while maintaining ethnic distinctions in its legislation.

The refusal to legally recognize the ethnic identity of the Ukrainian ethnocultural group, while preserving collective rights for selected non-Ukrainian communities and maintaining the absence of nationality registration, constitutes the implementation of legal apartheid, violating the principles of equality and the right of peoples to self-determination.