The Theory of the Mechanism for the Gradual Dismantling of the Collective Subjectivity of Peoples

Notably, in contemporary society, the topic of the rights of peoples has virtually disappeared from public and political discourse. Instead of discussing who truly holds power, who owns the territory, resources, and collective will, the media space is dominated by distracting topics — from the myth of “the state as a corporation” to debates on “the legal status of the individual” and human rights detached from the context of a people as the bearer of sovereignty.

In fact, the collective rights of peoples — as subjects entitled to self-determination, ownership of land, natural resources, and their own political institutions — have been replaced by individualized human rights. While human rights are enshrined in several international treaties and conventions (including the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights), they primarily address personal liberty and individual inviolability, without touching on issues of political authority, territorial entitlement, or collective ownership.

Thus, human rights are not equivalent to the rights of peoples. They do not protect the status of a collective as a source of power and bearer of sovereignty. Violations of individual rights may trigger diplomatic pressure — but violations of the rights of peoples constitute international crimes: aggression, colonization, apartheid, and the forcible denial of legal subjectivity. It is precisely this substitution of categories that has paved the way for dismantling the political subjectivity of peoples without formally revising international law.

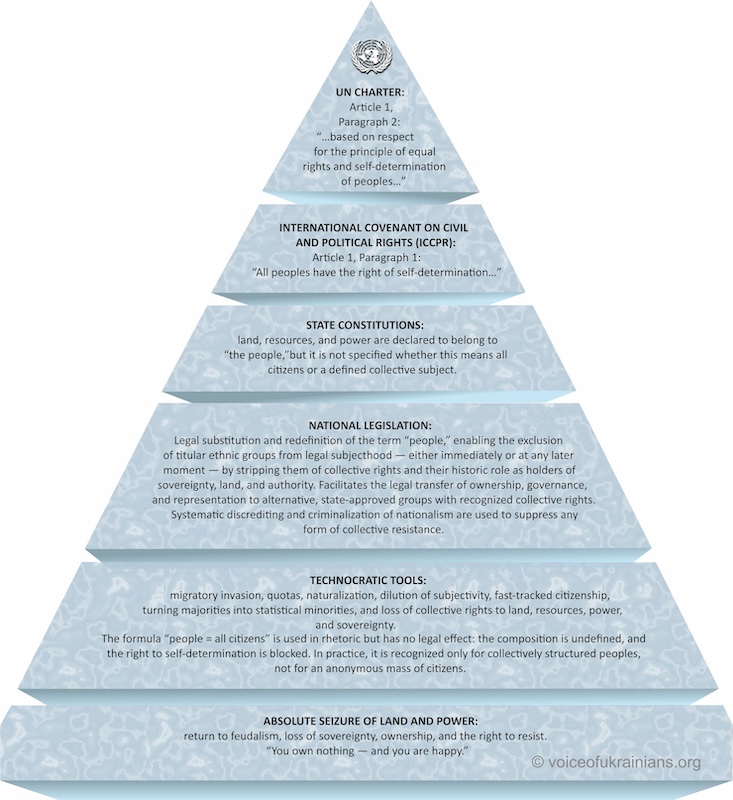

On the path to implementing the “2030 Agenda” of the World Economic Forum, with its goal of full control over territory, resources, and the very authority over society, there stood one fundamental obstacle: international law, which formally enshrines basic guarantees for peoples as bearers of sovereignty, land, and collective will.

This framework could not be abolished directly, nor could its repeal or rewriting be honestly justified without undermining the very appearance of legitimacy.

No one can openly declare that the UN Charter — particularly its first article — is no longer in effect, because it is this very article that enshrines the right of peoples to self-determination as a jus cogens norm.

Likewise, no one can publicly repudiate the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which reaffirms this same right and elevates it to a binding obligation for all states.

Nor can anyone simply erase from national constitutions the clause stating that land, subsoil, natural resources, and sovereign power belong to the people — because it is precisely this legal formula that distinguishes a free people from a managed, voiceless mass, that is, from a people reduced once again to the status of feudal subjects, stripped not only of property, but of authority over their own land and state.

After the fall of monarchies, the term “people” still implied a historical community — an ethnos with deep ancestral roots, a shared culture, and collective memory, rather than a faceless administrative mass. The formula “the people are the source of power” was initially interpreted literally: it referred to real individuals united by language, traditions, and the right to their land. Over time, however, the authorities turned this phrase into a convenient tool of manipulation. A strategy was implemented to transform the ethnic “people” into a depersonalized civil mass: first, through the legal substitution of concepts, where “people” as the bearer of sovereignty was opposed to “citizen” as a subject of subordination, akin to a subject of the crown; and second, through mechanisms of social engineering aimed at eroding ancestral continuity and ethnic identity by means of cultural and social mixing of the population. As a result of this process, cultural, linguistic, and ancestral bonds disintegrate, leaving the state as the sole unifying factor.

This dynamic reinforced the stability of the state apparatus by minimizing the risks of sudden self-determination or revolutionary movements, as civil society, deprived of organic cohesion, became fully subordinate to bureaucratic structures. Ultimately, this led to a de facto, albeit not formally legal, return to the principles of monarchical governance through technocratic instruments of control — a process that took nearly a century to complete.

The women’s rights movement of the 1920s was the first step in shifting the focus from the collective rights of the people to the individual rights of the citizen. Under the banner of equality, it not only granted women greater personal freedoms but also undermined the notion of family and kinship as the foundation of popular will. Historically, the family formed the collective “we” through which the people governed land, traditions, and social order.

In the 1960s–70s, the counterculture of the hippies, rejecting traditions and authorities, further eroded this foundation by establishing a cult of personal choice and freedom from any shared obligations. In the 1980s–90s, radical feminism pushed this trend to its limits, finally cementing the priority of individual rights over collective responsibilities. The people as a collective subject gradually dissolved into a mass of separate “I”s, connected not by common rights to land and power but by the administrative frameworks of the state. When everyone sees themselves only as a citizen and not as part of a people, the right to collective self-determination becomes an empty formality, and the real levers of power pass to bureaucratic structures.

The LGBT agenda, in its radical political form, acts as an internal sabotage mechanism against the collective rights of peoples. While migration destroys culture and social order from the outside, LGBT ideology fragments the people from within, erasing their collective “we.” Instead of a historical community built on family, kinship, and generational continuity, there emerges a set of individual “I” and “you,” deprived of shared responsibility and succession. In canonical and historical law, it is precisely family and kinship continuity that define a people’s right to land, resources, and power. When the collective structure is diluted and inheritance becomes abstract, the people cease to exist as a unified subject of law, replaced by a manageable technocratic mass.

Euthanasia, in its legalized forms, also undermines the foundation of collective rights because it strips the people of the role of guardian of life and continuity. By allowing a “right to die,” technocratic institutions effectively claim the authority to determine the value of human life and the moment of its end. This transforms life from an inviolable value into a managed resource, subject to regulation based on criteria of efficiency, humanity, or economic expediency. A people that surrenders this function ceases to be a collective subject capable of protecting its members, land, and heritage; it is replaced by a technocratic system where life and death become matters of algorithms and regulations.

The climate agenda is yet another tool for dismantling the collective rights of peoples, operating under the guise of a global “good.” Under the pretext of combating climate change, the right to manage land, subsoil, and natural resources is removed from the sphere of national sovereignty and the collective will of the people and transferred to supranational regulators, private funds, and corporations that bear no responsibility to the people. The formulas of national constitutions — “the land and subsoil belong to the people” — turn into fiction: decisions on extraction, distribution, and use of resources are made not at the level of the people, but within global agreements where the people’s subjectivity is not even recognized.

The pandemic and vaccination became tools for legalizing access to basic rights. Under the guise of caring for public health, the principle was introduced for the first time that freedom of movement, work, and social interaction is not an inherent right but a permission granted by state and supranational bodies upon fulfilling certain conditions. Without the pandemic, such restrictions would have triggered mass protests, but the sanitary pretext made them socially acceptable. Through this precedent, the people effectively acknowledged that their natural rights can be revoked by decree and depend not on collective will, but on administrative regulations and international structures.

As a result of these processes, the people lose not only resources but also power and are converted into conditional “tokens” — depersonalized units that can be manipulated and traded on global markets. Human resources become a commodity, deprived of the right to say “no” or to influence decisions made by technocratic structures under the pretext of “the common good.”

Notably, even in the most fundamental international documents — such as the UN Charter and the ICCPR — there is no legally codified definition of who exactly qualifies as a “people” entitled to the right of self-determination. This ambiguity remains unresolved to this day, despite dozens of conflicts and repeated appeals to these norms. As a result, arbitrary substitution is permitted: instead of an ethnic or historical community, the term “people” may be interpreted as an abstract aggregate of citizens — devoid of territory, collective will, or historical continuity. Such legal ambivalence does not protect rights; rather, it enables the exclusion of titular nations from legal subjectivity without formally violating international law.

It is precisely due to the absence of a clear definition of “people” within the context of international law that selective application of these norms becomes possible. In order to avoid formally violating the law, it is enough to exclude a specific group from the category recognized as a “people” — through redefinition, silent omission, or conceptual substitution. As a result, the right itself remains “in force,” but those who ought to benefit from it are removed from its jurisdiction. This is the core mechanism of dismantlement: exclusion without repeal.

It is precisely to enable such a substitution — to transfer power from peoples to technocratic mechanisms without triggering open resistance — that an indirect strategy is used: not to abolish rights, but to exclude those who once held them. Instead of a direct attack on international law, its bearer is removed — the people as a legal subject. Their status is blurred, redefined, or ignored, so that, formally, the rights remain in force, but in practice, they become inaccessible.

A technocratic system is a form of governance in which key decisions are not made by living individuals who bear political or moral responsibility, but by impersonal mechanisms: algorithms, automated regulations, social credit systems, and artificial intelligence. In such a system, it becomes impossible to appeal to any identifiable person or body with a question, complaint, or demand for justice. The response is always the same: “this is how the system works.”

The individual no longer acts as a representative of a people endowed with the right to collectively determine its fate. Instead, he becomes merely a citizen — subject to administrative procedures but lacking any real influence over power, resources, or societal choice. This means that the people effectively lose not only their right to self-determination but also the ability to defend their rights — because the subject capable of doing so no longer exists in legal form.

Formally, the right still exists, but it either no longer has a bearer, or it has become de facto reserved exclusively for those recognized as a distinct people with collective international subjectivity — most often small ethnic groups that have been granted special status and, in essence, a monopoly on exercising the right to self-determination, land ownership, and international representation.

In authoritarian states, the dismantling of collective rights has been carried out through legal substitution. The concept of “the people” is formally preserved in constitutions as the source of authority and owner of land and natural resources, but nowhere is it clearly defined — whether it refers to the aggregate of all citizens or to a specific historical community. This creates a legal trap: the people exist on paper, but most citizens are uncertain whether they truly belong to it.

Ambiguous formulations such as “the people” (in Ukraine’s Constitution) or “the multinational people” (in Russia’s Constitution) deliberately leave a legal gap between two possible interpretations: on the one hand, the people as a collective subject with the right to self-determination and sovereignty; on the other, the population as an administrative aggregate of individual citizens. This ambiguity allows political and media rhetoric to invoke the ideal of popular sovereignty, while in legal terms, there is no clearly defined bearer of collective rights. As a result, the right is formally proclaimed but lacks a concrete subject — and thus becomes unenforceable.

To fully grasp the consequences of erasing collective subjectivity, one need only look at the example of Ukrainian displaced persons. In public, media, and political discourse, they are systematically referred to as “refugees.” However, not a single Western country has granted them the corresponding legal status. Instead, they are placed under temporary protection schemes or classified as temporarily displaced persons. The fact that Ukrainians lack formal refugee status is deliberately concealed.

No Western politician, human rights advocate, or media outlet explains to their own citizens — the taxpayers — that millions of Ukrainians are not legally recognized as refugees. They are not granted the guarantees formally provided by the 1951 Refugee Convention: no protection from deportation, no right to permanent residence, and no pathway to citizenship. Instead, temporary protection is used — a time-limited status dependent on political discretion and offering no stable legal footing.

As a result, Ukrainians — like other legally unrecognized peoples with Ukrainian citizenship — are effectively held in a legal “grey zone”: states can extend or terminate temporary protection at any time without formally violating international obligations. Granting full refugee status would automatically imply recognition of these groups as a “people” entitled to the right of self-determination — which would contradict Ukraine’s own domestic legislation that excludes them from the category of collective rights holders.

This legal deadlock once again demonstrates that the problem lies not in isolated decisions, but in a coordinated architecture of legal control, where international and national law are used not to protect populations but to exclude them from mechanisms of protection. This is precisely what allows the technocratic system to function without directly violating norms: the law formally remains intact, but the bearers of rights are denied recognition.

Where the concept of “the people” could not be legally erased — in countries with relatively preserved democratic institutions, especially in Western Europe — another mechanism was introduced: mass migration and demographic engineering. Even if the formal status of the people remains, they are gradually reduced to a numerical minority, unable to exercise their legally enshrined right to determine policy or possess territory. Under democratic conditions, this results in a complete loss of influence: decisions are made by the majority, and the voice of the titular population becomes politically irrelevant. Along with this, ownership of land, subsoil, resources, and power de facto shifts to the state — or to supranational structures acting on its behalf.

This is how the mechanisms of dilution, quotas, accelerated naturalization, and artificial multinationalism work — they gradually turn any indigenous majority into strangers on their own land, depriving them of ownership, rights, power, and freedom. As a result, historical nations effectively become serfs — on their own territory.

A notable feature of the national constitutions of sovereign states is that they guarantee the equality of individual citizens, but remain silent on the equality of peoples and the distinction between the rights of a citizen and the rights of a people, thereby leaving a legal loophole for exclusion from collective legal subjectivity. In most cases, the constitution does not require equating a member of a people with a citizen, which makes it possible to treat their status differently — depending on political will or ethnic classification.

In the United States and the United Kingdom, wealth and power do not formally belong to “the people,” but to those who control the institutions — corporations, the stock market, big capital, IT, media, or, in the case of Britain, the monarchy.

But what holds this structure together? — Social consensus on the rules of the game:

The Constitution, electoral institutions, trial by jury, trade unions, tax discipline, and private property as a sacred foundation.

Mass migration undermines this consensus: people who did not participate in building the system are less likely to defend it passionately. They will not take to the streets to defend the First or Second Amendment. They want benefits and security — not abstract rights.

Gradually, such masses become more willing to accept a “new social contract” — for example: digital social credit systems, biometric surveillance, digital currencies, digital IDs, and so on.

This is not so much about the seizure of land or natural resources — it is about the dismantling of the very right to resist.

When there is no united “people,” there is no collective interest, no core of strength capable of saying “no” to global corporations or the state apparatus.

What remains is a mass, governed by algorithms and dependent on subsidies.

First, the United States spent decades opening its doors to millions of migrants. Then, the authorities deliberately allowed open legal and humanitarian chaos: mass deportations, detention of families, and even deportation of children born on U.S. soil.

All of this has been accompanied by demonstrative harshness and media escalation, intended to provoke internal protest, moral division, and associate immigration enforcement agencies (like ICE) with “fascism” and a new “Holocaust.”

This creates a pre-engineered social conflict: when resistance reaches its peak, the system will publicly “wash its hands,” admit its mistakes, and open new doors.

By then, a second wave of migration — even larger in scale — will face no resistance. A society torn apart and demoralized by its own reaction will no longer be able to regroup.

Step by step, this dismantles the civil contract that might still restrain the system.

In essence:

-

In Western Europe, migration erodes the titular landowner, the national core, and popular sovereignty.

-

In post-Soviet states, the titular landowner is stripped of status through the redefinition of the concept of “the people.”

-

In the U.S., the bearer of civil resistance is broken, class identities are fragmented, and the core capable of defending civil liberties is destroyed.

The result:

All three mechanisms lead to the same outcome: the unified core of resistance is replaced by fragmented individuals who can be absorbed into any new global contract — digital, climate-based, pandemic-related.

No one will say “this is our land” or “these are our rules.” Because “we” no longer exists.

1. Authoritarian Lawlessness (Post-Soviet and Partially Asian Bloc)

Mechanism: Direct exclusion of the titular nation or nations from the status of a collective subject through national legislation.

Examples:

Ukraine — this is not just about Law No. 1616-IX “On Indigenous Peoples,” but a whole chain of legislative steps that systematically dismantled the legal status of ethnic Ukrainians as a people. In the transitional period after gaining independence, the term “people of Ukraine” still referred to the historical ethnic group with rights to land, natural resources, and self-determination. However, in 1996, the Constitution introduced the formula: “the Ukrainian people are the citizens of Ukraine of all nationalities,” legally erasing the distinction between the titular nation and the administrative population.

In 2021, Law No. 1616-IX officially excluded ethnic Ukrainians from the list of indigenous peoples, recognizing only Crimean Tatars, Karaites, and Krymchaks.

In 2022, Law No. 2215-IX “On De-Sovietization” annulled all acts of the Ukrainian SSR and the USSR that had recognized the Ukrainian people as a historical subject with continuity and the right to sovereignty. As a result, over the course of 30 years, the titular ethnic group was transformed into an anonymous mass, whose only remaining “heritage” consists of mova, borscht, and vyshyvanka—but without the right to own their land or statehood.

Russia — the 2020 constitutional reform, presented as merely a “reset of presidential term limits,” in fact eliminated even the residual language of “sovereign statehood” and “federal treaty” from the constitutions of the republics. At the federal level, a vague term was enshrined: “the multinational people of the Russian Federation,” with no legal definition of a titular ethnic nation. All mentions of the statehood of the republics were removed from the Constitution, and their status was unified under the formula “subject of the Russian Federation.”

The final symbolic blow came in Tatarstan: in 2022, under Kremlin pressure, the republic was forced to remove the word “state” from its constitution and rename the position of “President of the Republic” to “Head of the Republic,” thereby erasing even symbolic sovereignty. This marked the total subordination of all titular peoples to the central authority, without the right to collective self-determination or international representation.

In essence: the titular people — or peoples — in Russia are deprived of a legally defined collective status and of the right to be the bearers of sovereignty. All territory, resources, and power are concentrated in the state, which governs them on behalf of an abstract “multinational people” or the undifferentiated sum of “all citizens.”

At the same time, Russia is implementing a hybrid model of dismantling collective subjectivity, combining authoritarian legal mechanisms with demographic strategies. On the one hand, through constitutional reforms and legal acts, the titular ethnic group is stripped of its right to collective self-determination.

On the other hand, external migration continues to grow: in 2024 alone, over 6.3 million migrants arrived in Russia, half of whom came for employment purposes. Further inflows are projected — including up to one million migrants from India.

In the absence of a recognized legal subject — a titular people — such a migration policy leads to demographic dilution, erodes the cultural core, and renders any form of national consolidation impossible.

Thus, the Russian system fuses Western instruments of demographic dissolution with internal legal nullification — resulting in the transformation of the people into a managed mass with no structure, no rights, and no sovereignty.

International law protects not individuals, but peoples. This is a fundamentally important point that is rarely stated directly. The core universal treaties — the UN Charter (Art. 1), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Art. 1), the Genocide Convention, and other foundational instruments — define collective rights specifically for peoples as subjects of international law: the right to self-determination, the right to ownership of natural resources, and the right to international protection and representation.

In contrast, citizens, as individual persons, are protected only by national law, primarily the constitution of a given state.

This creates a systemic vulnerability: if a state legally excludes a certain group from the status of a “people” — substituting it with the concept of “all citizens” — it effectively removes that group from the scope of international legal norms. They can no longer be classified as a subject entitled to collective rights under international law. They become an administrative population, subordinate to the state but lacking access to mechanisms of international legal protection.

Such a substitution is particularly dangerous in contexts of internal violence or conflict, as the excluded group no longer falls under the protections designed to safeguard peoples from discrimination, genocide, or enslavement.

This is the essence of the legal trap: international law remains formally in effect, but its intended subject — the people — is removed from the system itself.

Thus, when Russia, in 2020, eliminated the statehood of its republics and stripped titular peoples of legal subjectivity, and Ukraine, in 2021–2022, legally excluded ethnic Ukrainians from the list of indigenous peoples and historical succession — these were not merely domestic reforms.

They constituted a de facto removal of these groups from the jurisdiction of international law.

This strips them of access to the right to self-determination, to international protection, and to legal recognition of collective harm.

From a legal standpoint, such steps lay the groundwork for impunity in the use of violence, repression, and forced mobilization — because the very subject entitled to international protection has been erased.

2. Western European model (EU democracies)

Mechanism: mass migration and multiculturalism as tools to dilute the titular group.

Examples: Germany, France, the Netherlands, Sweden.

Essence: the historical majority is transformed into one of many fragmented “groups,” losing its demographic advantage and the ability to collectively assert rights over land, natural resources, or reparations. Legally, “the people” formally remain in national constitutions, but de facto dissolve among migrant diasporas.

Result: territory and resources are governed by the state and supranational structures (EU, WEF, IMF), while the titular majority slowly disappears or dissolves.

3. Anglo-American corporate form (monarchies and imperial systems)

Mechanism: migration and multiculturalism are not used to dilute legal titles (which most of the population never had to begin with), but to erode the cultural framework and value identity of the historical core.

Examples: United Kingdom (where everything formally belongs to the Crown), United States (where land and resources de facto belong to corporate-state trusts and financial groups).

Essence: migrants and multiculturalism dismantle the traditional way of life, so the native majority is left without a stable identity on which to base resistance. Without a collective cultural framework, there is no collective will— and the entire system of governance shifts into the hands of corporate and administrative apparatuses that redistribute resources through debt models, tokenization, and control over infrastructure.

Conclusion:

One of the least discussed but most accurate indicators of future violence is the prior exclusion of an ethnic or national group from the status of a “people.” This does not always occur openly: sometimes a group appears to be included in constitutional language, but in practice is stripped of collective rights through legal manipulation — such as refusal to ratify international conventions, selective recognition of “indigenous peoples,” or semantic substitutions in legislation. As a result, not only the bearer of rights disappears, but also the holder of historical continuity and legal responsibility. And when there is no recognized peoples — there is no recognized crime committed against them.

It happened in Rwanda, where the Tutsi were not officially recognized as a people before the 1994 genocide, and were portrayed in propaganda as “enemies of the state” or “vermin.” It happened in Myanmar, where the Rohingya were for decades classified as “illegal migrants,” denied citizenship, and excluded from the list of recognized ethnic groups — creating a legal loophole that enabled the ethnic cleansing of 2017. The same occurred in Syria, where Kurds were denied citizenship en masse before the war and had no recognized rights to land or cultural autonomy. In Yugoslavia, the dilution of the legal status of republics and peoples prior to the breakup led to bloody conflicts, where the absence of clear legal subjecthood made ethnic violence easier to justify.

The clearest historical confirmations of this pattern is the Holocaust. During World War II, the Nazi regime systematically targeted two main groups for total physical annihilation: the Jews and the Roma (Gypsies). What united both cases was not shared ethnicity, but the fact that neither group was legally recognized as a sovereign people under international law. They possessed no statehood, no formal institutions, and no collective subjectivity that could trigger protective mechanisms under international norms. This made them particularly vulnerable to dehumanization and extermination. Yet only one of these peoples — the Jews — succeeded in restoring their collective legal status after the war, through the creation of the State of Israel and the international recognition of the Jewish people as a distinct subject of rights.

In contrast, the Roma, despite being victims of genocide, were never granted such recognition and remain without meaningful collective rights, reparations, or representation to this day. This contrast illustrates a legal reality: only peoples who possess, or are able to restore, legal subjectivity can claim justice. Those who lack it — can be destroyed without legal consequence.

A similar scheme was implemented in the Soviet Union, where Ukrainians, Russians, Belarusians, Kazakhs, and other titular peoples were deliberately dissolved into the faceless category of the “Soviet people.” This was not mere rhetoric — it was a deliberate legal strategy designed to erase collective subjecthood. As a result, neither the Holodomor, nor the mass deportations of Crimean Tatars, Chechens, and Ingush, nor the execution of Polish officers, nor the Gulag system with millions tortured and killed — were ever recognized under international law as acts of genocide against specific peoples.

This means that tens of millions of victims remained nameless not only in memory, but in law. None of these crimes received the legal recognition that was granted to the Holocaust. Not because the scale was smaller — in some cases, it was even more horrifying — but because the peoples who perished had been stripped of legal subjectivity. They had no institutions to speak on their behalf. No international representation. They were not recognized as “a people” in the legal sense — and therefore, under international law, nothing had officially been done to them.

This is the most insidious form of genocide: one that cannot be recorded, because not only the person is destroyed, but the very right to be named as a collective victim. These were dozens of invisible Holocausts that never received tribunals, reparations, or even formal recognition. People were killed, exiled, starved, burned — but in the eyes of international law, it remained a statistic: without a name, without a subject, without a crime.

Why? Because there was no formally recognized subject capable of declaring a crime on its behalf.

This example clearly demonstrates why collective rights must not be tied to the state. States rise and fall, borders shift, regimes collapse — but the people, their ethnic and historical identity, remain. It is the people — not the temporary state — who must be recognized in international law as the bearer of rights and the subject of protection. Otherwise, when the state disappears, so do all the crimes committed against its people.

This contrast illustrates a fundamental truth: when a people is legally dissolved into the mass of “citizens” or “population,” violence against them becomes invisible in the eyes of international law.

If no people exists, then no crime can be named against it.

That is why restoring the legal collective subjecthood of a people is not a formality or an ideology. It is a matter of survival, of historical memory, and of legal protection against the repetition of the worst atrocities.

Based on the above, believing that Putin and Zelensky truly represent opposing camps means failing to grasp the core issue. Both are merely figures within a shared global process, where wars and conflicts serve only as a smokescreen for dismantling the collective rights of peoples.

This mechanism operates not only in Russia or Ukraine — it has been launched globally, using different instruments but always leading to the same outcome: the people are stripped of their right to own what was recently still considered their collective property.

To resist this by force is futile — because the power of states and transnational structures vastly outweighs any fragmented protest movement.

The only real path forward is to reclaim collective subjectivity on a legal level — to reassert the word “we” not as a slogan, but as a status codified in rights that cannot be erased by a simple law or diluted by mass migration.

After World War I, between 1917 and 1922, nearly all European monarchies collapsed: the Russian Empire (abdication of Nicholas II in 1917), the German Empire (Kaiser Wilhelm II fled in 1918), the Austro-Hungarian Empire (fall of Charles I in 1918), and the Ottoman Empire (removal of Mehmed VI in 1922). Power formally transferred to the people: republics, constitutions, and parliaments emerged, enshrining the principle of popular sovereignty. For the first time, the people were recognized as the source of power, and as owners of land and resources. However, this very idea — the people as bearers of collective rights — became too dangerous for old and new elites alike, who sought to regain control through supranational institutions, bureaucratic systems, and financial tools.

After the Holocaust, Jewish nationalism became the only one to receive international recognition and protection from discreditation. This is due to the fact that the tragedy of the Holocaust became a legal precedent: the world acknowledged the right of the Jewish people to national self-determination, statehood, and collective protection, while the national movements of other peoples were gradually stigmatized and deprived of similar legitimacy.

A modern illustrative example of how nationalism can protect nations from external governance is the WHO pandemic agreement. On May 20, 2025, at the 78th session of the World Health Assembly, it was supported by 124 countries, with no votes against, while 11 states (Poland, Israel, Italy, Slovakia, Iran, Bulgaria, Egypt, Jamaica, the Netherlands, Paraguay, and formally — Russia) abstained, and the USA and Argentina refused to participate altogether. In most of these countries, nationalism — in the legal sense of recognizing the people as a subject — is still preserved and capable of influencing political decisions. Russia, however, abstained not by the will of the people but due to geopolitical games and government rhetoric. Where the nation has been dissolved into the category of “citizen” and technocratic instruments have already been implemented, there is no one left to express collective dissent, and decisions are made without public resistance and even without the possibility of appeal.

A modern and striking example of how nationalism can protect peoples from external governance is the WHO pandemic agreement. On May 20, 2025, at the 78th session of the World Health Assembly, it was supported by 124 countries, with none voting against, while 11 states (Poland, Israel, Italy, Slovakia, Iran, Bulgaria, Egypt, Jamaica, the Netherlands, Paraguay, and formally — Russia) abstained, and the United States and Argentina refused to participate altogether. The exception of Russia here is symbolic: its abstention is not an expression of the collective will of the people, but rather an element of geopolitical rhetoric, whereas in other countries the decision reflects the real preservation of national identity and the political subjectivity of the people. In contrast, where the nation has been dissolved into the category of “citizen” and technocratic instruments are already in place, there is no one left to express collective dissent, and decisions are made without public resistance or the possibility of appeal.

The right of peoples to self-determination — that is, the right to liberty and to choose their political, economic, and cultural destiny — is one of the highest norms of international law. This right is enshrined as a peremptory norm (binding on all states without exception) in Article 1 of the UN Charter, as well as in Article 1 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

However, in practice, the realization of this right is effectively blocked. In many countries, the concept of “the people” is either undefined in legislation or substituted with the formula “all citizens.” This substitution often occurs not through formal legal documents, but through political rhetoric, media discourse, and educational programs. Such narratives blur the understanding of who actually holds sovereignty — who has the right to govern territory, resources, and state institutions.

Legally, the principle of direct equality between a citizen and a people is enshrined only in a few countries (such as France), while in most cases, ambiguity prevails — stripping peoples of their collective rights. Any attempt to restore the subjectivity of a people — as a collective bearer of the right to self-determination — is discredited through accusations of extremism, fascism, ethnocentrism, or xenophobia. As a result, the right remains on paper, but practically unattainable. And this, in essence, is the dismantling of one of the core principles of the international legal order.

Thus, in the span of a century, the idea of popular sovereignty — born from the ruins of empires — was first discredited by Nazism, then replaced by internationalism, and is now culminating in a technocratic scheme that leads to the very scenario outlined by the World Economic Forum:

“You will own nothing. And you will be happy. Everything you need will be rented — and delivered by drone.”