Apartheid of Ukrainians and the Hidden Interethnic Conflict

Under the cover of external aggression, a legal regime was established in Ukraine that exhibits features of institutionalized apartheid and interethnic conflict. The largest ethnic group — Ukrainians — has been stripped of status, collective rights, mechanisms of international protection, and even the possibility of legal self-preservation. These changes were deliberately enshrined in national legislation under martial law, indicating a conscious shift in focus from external threat to internal reconfiguration of the sovereign subject.

While formally appealing to the idea of national unity, the state manipulates the concept of “the people” by exploiting constitutional ambiguity between the collective sovereign and the totality of citizens. Depending on political expediency, the authorities arbitrarily alternate between these constructs, excluding Ukrainians from all forms of ethnically defined legal subjectivity. This substitution enables the redistribution of collective rights in favor of groups recognized as “indigenous” or “minorities,” while entirely ignoring the titular ethnicity.

1. What is apartheid

According to Article 7(2)(h) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998):

Apartheid means “inhumane acts… committed in the context of an institutionalized regime of systematic oppression and domination by one racial group over any other racial group or groups and committed with the intention of maintaining that regime.”

Key characteristics:

• Institutionalization

• Systematic nature

• Oppression based on ethnic identity

The Republic of South Africa provides the historical precedent: under apartheid, “Black representatives” could sit in parliament, but this did not signify recognition of Black people as a people. They were excluded as a collective subject. The same is occurring in Ukraine today with respect to ethnic Ukrainians.

Clarification: who qualifies as a “racial group”

In international law, the concept of a “racial group” is not limited to skin color.

According to Article 1 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, it includes:

“any distinction based on race, color, descent, or national or ethnic origin…”

This interpretation has also been confirmed by international judicial practice (e.g., Rwanda cases), where conflicts between closely related ethnic groups were recognized as racial discrimination.

Therefore, apartheid may occur even between groups of the same “race” — if the state system creates a legal and institutional hierarchy between them.

2. Definition of Interethnic Conflict According to the OSCE and Its Applicability to Ukraine

According to the Guidelines on Conflict Prevention by the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities:

Inter-ethnic conflict is defined as “a state of tension between ethnic groups arising from systemic inequality in the realization of collective rights, including limited access to political representation, discrimination, and threats to cultural and linguistic identity.”

According to OSCE standards, the key legal criteria of an inter-ethnic conflict include:

-

Legalized inequality between ethnic groups in the realization of fundamental rights.

-

Exclusion of a group from mechanisms of decision-making at the state or regional level.

-

Absence of legal guarantees for the preservation and development of ethnocultural identity.

-

Inability to establish institutions of ethnic self-governance where such rights exist for other groups.

These provisions are detailed in the Bolzano/Bozen Recommendations on National Minorities in Inter-State Relations, which emphasize:

“Systematic exclusion of an ethnic group from mechanisms of collective rights protection creates conditions for latent forms of inter-ethnic conflict” (Section II, para. 14).

In the context of Ukraine, the situation in which certain ethnic groups are deprived of equal access to political participation, the management of natural resources, or mechanisms of representation corresponds to the criteria of an inter-ethnic conflict under OSCE standards — despite the formal protection of cultural rights such as language or traditions.

Why this applies to Ukraine:

• Ethnic Ukrainians are officially excluded from all forms of collective representation (they are recognized neither as a “people,” nor as a “minority,” nor as “indigenous”)

• They lack the right to land, access to natural resources, repatriation, ethnic self-governance, and protection from the state as a recognized community.

• Meanwhile, such rights are granted to other groups (indigenous peoples and minorities)

• This creates a persistent structural asymmetry in which the titular ethnicity is denied access to the same rights afforded to others

• This situation generates conflict between formally equal citizens — rooted in ethnic affiliation, not civil status

This is a textbook case of interethnic conflict according to OSCE standards — and it is institutionalized at the legislative level, not limited to everyday societal discrimination

3. The Legal Substitution of the Concept of “People”

The Ukrainian state has officially enshrined in law a legal definition of ethnic Ukrainians as excluded from the status of a national minority. Article 1 of Law No. 2827-IX “On National Minorities (Communities) of Ukraine” explicitly states:

“A national minority (community) is a stable group of citizens of Ukraine who are not ethnic Ukrainians…”

Thus, it is legally established that ethnic Ukrainians cannot be recognized as a national minority, while all other groups are granted special rights — such as cultural autonomy, participation in international institutions, and protection from assimilation and discrimination.

This definition, by itself, constitutes direct evidence of discrimination, as it excludes an entire ethnic group from the system of legal protection based on ethnic origin. Such a provision violates Article 24 of the Constitution of Ukraine (prohibition of discrimination based on ethnicity).

At the same time, ethnic Ukrainians are not recognized as a people (in the international legal sense), nor as a minority, nor as an indigenous people, and therefore are deprived of all forms of collective legal subjectivity provided for by Laws No. 1616-IX, No. 2827-IX, and international standards. This creates a closed system of legal exclusion and violates fundamental principles of equality enshrined in both Ukrainian and international law.

This substitution of the concept of “people” is reinforced by judicial practice, in which court decisions are issued “in the name of Ukraine” — in the name of the state, not the people, as codified in procedural statutes, despite Article 5 of the Constitution, which proclaims the people as the bearer of sovereignty. In democratic systems, courts act in the name of the people or their representative:

-

In Germany: Im Namen des deutschen Volkes (“In the name of the German people”)

-

In France: Au nom du peuple français (“In the name of the French people”)

-

In the United States: The People v. X

-

In Poland: W imieniu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (“In the name of the Republic of Poland”)

-

In Hungary: A Magyar Köztársaság nevében (“In the name of the Republic of Hungary”)

Ukraine, though declared a republic in Article 1 of its Constitution, does not use the formula “in the name of the republic,” thereby removing the ethnic majority from judicial authority and reinforcing a legal abstraction of the state reminiscent of colonial or monarchical models.

The judicial reform initiated by Law No. 1402-VIII of June 2, 2016, institutionalized a disconnect between the judiciary and the principle of popular sovereignty as enshrined in Articles 1 and 5 of the Constitution of Ukraine. As part of this reform, the official name of the highest judicial authority was changed: since 2021, following the enactment of Law No. 1629-IX of July 13, 2021, the first part of Article 37 was repealed, and the court is now officially referred to simply as the “Supreme Court”, omitting any reference to the state affiliation (“of Ukraine”). This removal eliminates any reference to the people as the source of power and departs from democratic standards, under which courts act “in the name of the people.”

Furthermore, the appointment of judges takes place without the participation of the people or their representative institutions (Articles 126–129 of the Constitution of Ukraine). Since 2019, the procedures for judicial selection and oversight have been influenced by international bodies (see Law No. 193-IX of December 19, 2019). Judicial system funding also partially depends on external sources (Articles 130–132), further underscoring its institutional detachment from internal sovereignty.

The exclusion of ethnic Ukrainians from all forms of collective legal subjectivity—while simultaneously granting such rights to other ethnic groups—constitutes deliberate ethnic differentiation in access to rights, resources, and legal protection. Deprived of recognition as a people, minority, or indigenous group, ethnic Ukrainians lack the right to collective self-governance, international representation, or legal standing as a group. At the same time, threats to revoke citizenship for refusal to comply with military mobilization create a system of politically motivated exclusion from the legal order. This practice directly violates Article 5(d)(iii) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which prohibits any restrictions on the right to nationality based on ethnic origin, and also breaches Article 12(4) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Combined with the denial of access to mechanisms of governance, representation, and sovereign resource allocation, this policy meets the qualifying criteria of apartheid under Article 7(2)(h) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court—as a form of institutionalized domination and legal expulsion.

Ukraine ratified the Rome Statute on August 24, 2024, but with a 7-year deferral of its application. This means the state is legally shielded from liability for apartheid until 2031. Such a delay serves as direct evidence of intent to avoid international jurisdiction while consolidating a regime of ethnic exclusion without risk of criminal prosecution.

4. Why the Exclusion of Ukrainians Is Unique

The objection that in democratic states such as France the ethnic majority does not hold an explicit legal status overlooks a crucial distinction. In France, the Constitution (Article 1) equates citizenship with the people, guaranteeing the French as the primary ethnic group both cultural and material rights, including access to national resources. The Constitution of Ukraine does not establish such equivalence. The preamble interprets “the people” as the totality of all citizens, not as an ethnic group, and Article 5, which proclaims the people as the source of power, remains declarative, providing no legal status to ethnic Ukrainians. This lack of equivalence — “citizen = people” — is the root of the legal exclusion that leaves Ukrainians vulnerable in disputes over resources or territory.

In Germany, the Federal Law on Expellees and Refugees (1953) grants ethnic Germans the right of repatriation even without citizenship, while in Israel, the Law of Return (1950) provides Jews the right to immigrate and access state resources. These countries protect the ethnic majority as part of the people through the institution of citizenship.

In Ukraine, ethnic Ukrainians are excluded from collective legal subjectivity by Laws No. 1616-IX (2021), No. 2827-IX (2022), and No. 4662-IX (2023), as they are not recognized as a people, a minority, or indigenous. Their only legal bond with the state is citizenship, the loss of which strips them of all rights — unlike indigenous peoples (Crimean Tatars, Karaites, Krymchaks), who retain a right to repatriation. The interpretation of Article 5 of the Ukrainian Constitution, which declares the people as the source of power, has no force against these laws, especially in disputes over resources or territorial rights. Public rhetoric that questions one’s “Ukrainianness” based on failure to fulfill state obligations further increases the risk of citizenship deprivation, violating Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Such legal inequality reinforces apartheid under Article 7(2)(h) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

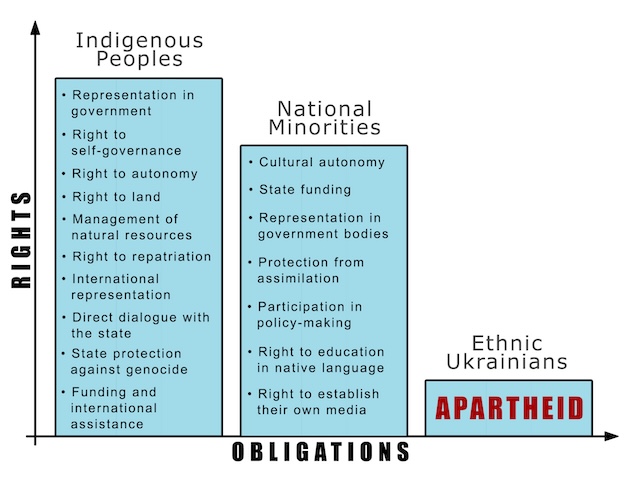

5. Rights Granted to Others — But Not to Ukrainians

A comparative list of rights enshrined in Ukrainian legislation:

Indigenous Peoples:

• Right to autonomy

• Right to self-governance

• Representation in government

• Direct dialogue with the state

• International representation

• Right to land

• Control over natural resources

• Repatriation

• State protection from genocide

• Funding and international assistance

National Minorities:

• Cultural autonomy

• State funding

• Representation in public institutions

• Protection from assimilation

• Participation in policymaking

• Right to education in native language

• Right to self-identification

• International relations and support

• Cultural centers and advisory bodies

Ethnic Ukrainians:

• Do not possess any of the above collective rights

• Are not subjects of international protection

• Are not mentioned in any special law as a collective ethno-cultural community

• Any form of collective self-organization is treated as a threat to “national unity”

6. Why the Presence of Ukrainians in Government Does Not Disprove Apartheid

A common counterargument claims: if Ukrainians are the largest ethnic group and present in parliament and civil service, how can there be apartheid?

The answer:

• Ethnic Ukrainians in government serve as individuals or as deputies from territorial districts, not as representatives of a people or ethnic group

• They have no institutional mechanism for collective representation

• Their status as a people is nowhere recognized in law — unlike minorities and indigenous peoples

• This is similar to apartheid-era South Africa: individual participation is no substitute for collective rights

7. Violations of International Law

The legal exclusion of ethnic Ukrainians violates:

• Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), guaranteeing rights of ethnic groups

• The Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (Council of Europe)

• Article 2 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

• Article 1 of the UN Charter, affirming the right of peoples to self-determination

• Article 7 of the Rome Statute — as institutionalized ethnic oppression (apartheid)

• The Genocide Convention — in terms of cultural and political destruction of an ethnic group

8. Indicators of Apartheid in Ukrainian Law

• Legal classification based on ethnic criteria

• Exclusion of Ukrainians from subjects of international human rights protection

• Absence of collective rights (to education, self-governance, culture)

• Forced assimilation through reforms

• Repression for asserting Ukrainian identity

• Forced conscription — without legal subjectivity and without the right to evacuation

• Denial of representation in international bodies

9. The Threat of Legal Exile Through Denial of Citizenship

Since 2022, Ukrainian political discourse has increasingly featured statements centered on the rhetoric: “If you don’t want to fight — renounce your citizenship.” This position — voiced even by former President Zelensky — is becoming an unofficial doctrine: refusal to mobilize implies voluntary forfeiture of citizenship. In effect, civil society is being prepared for such a scenario, despite the following legal gaps:

• There is no repatriation law.

• There is no legal mechanism to renounce citizenship without losing fundamental rights.

• Mass mobilization is carried out without recognition of Ukrainians as a sovereign people.

This creates a specific form of legal exile: individuals, though formally citizens, are deprived of the essential attribute of citizenship — recognition as part of the sovereign people — effectively turning the titular nation into ethnic hostages:

• They are denied the right to collective self-determination.

• They are denied the right to refuse forced subjugation.

• At the same time, they are burdened with guilt and threatened with exile for refusing to participate in actions carried out in the name of a state that does not recognize them as legal subjects.

This approach violates:

• Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality”)

• Provisions of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance

• And creates conditions for depopulation — as a form of genocide through legal marginalization.

The situation is further aggravated by the threat of citizenship revocation for refusing forced participation in war, while no safe exit or repatriation option is provided.

10. Recognition of Indigenous Peoples as a Mechanism for International Compensation

In the context of growing discussions about a potential revision of the outcomes of the USSR’s dissolution and possible restoration of union-state structures, Ukraine’s Law No. 1616-IX takes on additional, strategically significant meaning.

At first glance, it appears to be an internal human rights measure. However, from the perspective of international law, it functions as a legal safeguard that secures long-term rights and privileges exclusively for those groups officially recognized as “peoples” before any transformation of state sovereignty.

According to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007), such peoples are entitled to:

• compensation for historical injustices (such as deportations, colonization, cultural destruction);

• reparations, if restitution is not possible;

• international representation, even in the event of state sovereignty being lost.

These rights do not depend on citizenship, place of residence, or current political authority, provided the group was recognized as a “people” before the change in the state’s status.

Examples of international practice:

• Germany continues to pay compensation to Holocaust victims and their descendants, regardless of their current citizenship.

• Canada transferred billions of dollars to Indigenous communities for the loss of children and forced assimilation.

• New Zealand guarantees Māori parliamentary quotas and access to land funds.

• Australia officially recognized Aboriginal land rights.

• The United States grants federally recognized tribes the right to autonomy, independent courts, and government funding.

How this works in the Ukrainian context:

If Ukraine loses sovereignty or comes under external administration, it is the Crimean Tatars, Karaims, and Krymchaks — as officially recognized indigenous peoples — who retain legal subjectivity and can claim:

• compensation for colonization, deportation, and discrimination;

• international representation in UN bodies;

• restitution of property or resources;

• special status in new union-type structures.

And ethnic Ukrainians?

• Not recognized as a people.

• Not included in the category of national minorities.

• Not granted indigenous status.

• Excluded from all legal forms of ethnocultural subjectivity.

As a result, under any legal scenario — whether Ukraine continues to exist or is restructured — ethnic Ukrainians are left without international mechanisms of protection.

The legal paradox:

• Small groups numbering in the tens of thousands (including diasporas in Israel and Turkey) gain access to lifelong compensation mechanisms.

• Meanwhile, millions of people who identify as the Ukrainian people have no rights, no legal subjectivity, and no protective mechanisms.

This is not a theory, but a fully developed international legal scenario. With a single law in place and the complete absence of mechanisms for self-identification for the majority group, a no-lose structure has been created:

• If the state survives — Ukrainians are excluded from popular sovereignty.

• If the state dissolves — recognized peoples receive compensation.

• And Ukrainians remain legally nonexistent.

11. Conclusion

The legal framework established by Laws No. 1616-IX and No. 2827-IX, along with Ukraine’s refusal to ratify ILO Convention No. 169, has entrenched a system of apartheid and institutionalized interethnic conflict within Ukrainian law. The largest ethnic group — ethnic Ukrainians — has been excluded from all internationally recognized forms of ethnic subjectivity (people, minority, indigenous people), as well as from the system of collective rights: language, education, self-governance, cultural autonomy, international representation, and legal protection mechanisms.

This violates:

• Article 7 of the Rome Statute (apartheid)

• Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

• Articles 1 and 2 of the UN Charter (right of peoples to self-determination)

• Article 2 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

• Provisions of the Council of Europe Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

Particular attention should be paid to the legal paradox:

– At the international level, ethnic Ukrainians are recognized as a people (in the context of Ukraine’s existence as a national state of Ukrainians, its UN membership, and international representation);

– But at the domestic legal level, they are deprived of any mechanism for realizing this status.

While other ethnic groups are directly defined (as “indigenous” or “minorities”) and granted access to collective rights, Ukrainians are placed in a legal vacuum — without tools for self-determination, collective representation, or protection.

Moreover, institutionalized threats of citizenship revocation for refusing mobilization, the absence of a repatriation law, the impossibility of renouncing citizenship without forfeiting rights, and forced involvement in war without legal subjectivity — all form a unique mode of legal pressure and expulsion.

Effectively, this turns the titular nation into ethnic hostages:

• They cannot collectively self-determine

• They cannot refuse forced subjugation

• Yet they are assigned guilt and threatened with exile for refusing to act on behalf of a state that denies their subjectivity

This approach violates:

• Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality”)

• Provisions of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance

• And creates conditions for genocide in the form of life circumstances intended to partially destroy an ethnic group physically and legally — through marginalization, depopulation, and cultural erasure

This situation demands an urgent international legal response:

– Recognition of ethnic Ukrainians as a people

– Restoration of their subjectivity and collective rights

– Elimination of legal asymmetry

– International investigation into the presence of elements of genocide

Without this, Ukraine will remain a state with codified legal apartheid and a concealed interethnic conflict — whose consequences may escalate into more severe forms of internal violence and legal collapse.

Unconditional support for such a regime by foreign states and organizations, without proper analysis of its legal implications, may constitute complicity in and facilitation of a system that violates fundamental norms of international law — including the Rome Statute, the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, and the Genocide Convention.

Disclaimer

This text is an analytical study of the legal norms of Ukraine and their consequences for the ethnic identity, subjectivity, and international protection of ethnic Ukrainians. It is not directed against any ethnic group, religion, or culture. All referenced legislative acts are examined solely from the perspective of their legal content and their implications for the system of popular sovereignty and equality.

We categorically condemn all forms of xenophobia, and discrimination and stand for equal rights for all peoples. The purpose of this publication is to defend the rights of ethnic Ukrainians as a people and to restore a fair legal balance within the framework of international and constitutional norms.

This material was prepared by a non-lawyer, yet the information presented in this article has, at the time of publication, neither been refuted nor confirmed through any formal legal process — despite the fact that dozens, perhaps even hundreds, of professional lawyers have already reviewed the materials on this site. To date, none of them have provided a public legal assessment — either in support or in opposition.

Therefore, the facts and conclusions presented herein remain relevant within the scope of open and accessible analysis.

This material has been created as part of a lawful legal resistance to arbitrariness, signs of genocide, and in the exercise of the right to individual and collective self-defense, in accordance with:

• Articles 1 and 2 of the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948)

- These articles obligate states to prevent and punish genocide. Article 2 defines genocide as acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.

• Articles 1, 19, and 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, 1966)

- Article 1 affirms the right of all peoples to self-determination and to freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources.

- Article 19 guarantees the right to freedom of opinion and expression.

- Article 20 prohibits war propaganda and advocacy of national, racial, or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility, or violence.

• Article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998)

- Defines crimes against humanity, including persecution of ethnic groups, deportations, enforced disappearances, and other forms of systematic violence.

• Article 51 of the UN Charter

- Recognizes the inherent right of individual and collective self-defense in the event of an armed attack or existential threat.

• Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)

- Guarantees the right to own property — both individually and collectively — and protection against arbitrary deprivation, including the cultural, linguistic, and political heritage of a people.

Should any clarifications, well-grounded objections, or alternative legal interpretations emerge in the future, the author is open and willing to consider them respectfully. Please contact the website administration — any factual errors will be corrected, and, if necessary, an official public clarification or apology will be issued.

Until professional legal critique is presented, the materials provided shall be regarded as a good-faith contribution to open public discourse.

The author of this material is not a nationalist, patriot, or member of any political party or ideology. This research does not aim to elevate any ethnic group over others and is not intended to undermine the territorial integrity of Ukraine. In the context of the text, the term “ethnic Ukrainians” refers to all autochthonous ethnocultural groups historically residing in the territory of Ukraine that are not officially recognized by the state. These include Boykos, Hutsuls, Lemkos, Rusyns, Volynians, Podolians, Polissians, Slobozhans, Chernihivians, Carpathian highlanders, Steppe dwellers, and others. This publication is a form of legal response to institutionalized inequality, independent of political affiliation, and is aimed at restoring the universal principles of legal subjectivity, equality, and international legal protection. The right to self-determination, collective representation, and protection from discrimination must be ensured for all ethnic groups of Ukraine without exception, regardless of their current legal status.

The author unequivocally condemns the armed aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine, the occupation of Ukrainian territories, war crimes, terrorist attacks, and any attempts to undermine Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

The Russian state, as an aggressor and occupier, holds no moral or legal authority to use this material in any form. Any attempt to exploit this text within Kremlin propaganda or information warfare is a deliberate manipulation, a distortion of its content, and a misuse of human rights language. Such interpretation contradicts the core purpose of this document, which is solely aimed at addressing internal legal discrimination in Ukraine in order to strengthen its democratic and legal foundations.